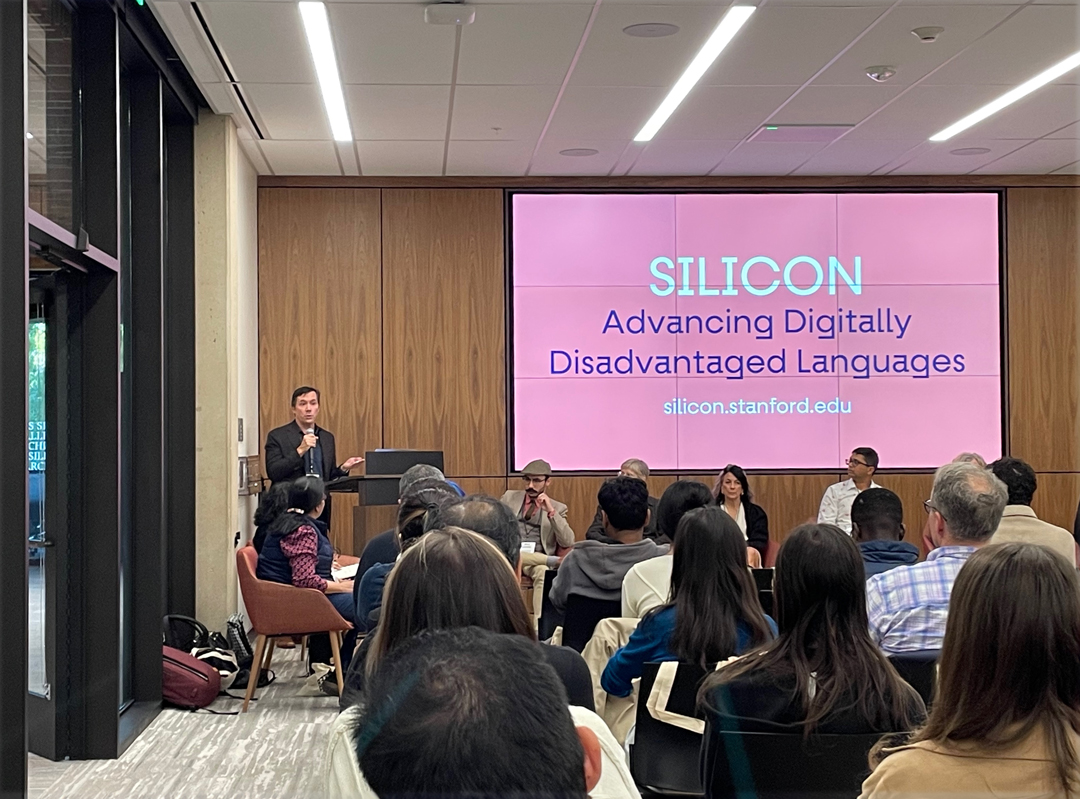

On October 27, 2023, at Stanford University, Tom Mullaney and his co-conspirators launched the SILICON initiative at an event entitled “Encode/Include.” This fairly brief kick-off was a prelude to the “Face/Interface” conference coming up at the beginning of December, which will launch SILICON in a more formal way. The acronym stands for “Stanford Initiative on Language Inclusion and Conservation in Old and New Media.”

What does all this mean? It’s a concerted effort to coordinate efforts around the world to catalog languages and writing systems that have been persistently sidelined or ignored and make them available for contemporary use. This means not just preserving languages or writing systems, but working to get them included in the Unicode standard and in other forms that make it possible for their speakers to use them in everyday life: for example, in texting on their phones. It also includes encoding so-called “dead” languages into Unicode so scholars and scientists can represent ancient manuscripts in a readable digital form. Thus the title: “Encode/Include.”

The October event, held in the Silicon Valley Archives at Stanford’s Green Library, was an intense hour-and-a-half round table of presentations and dialog among almost a dozen experts in different aspects of encoding language. The conversation was fluid and wide-ranging; it served to begin defining the problems rather than suggesting solutions. With “Digitally Disadvantaged Languages” (DDLs) encompassing 97% of all living languages around the world, the challenge is both daunting and inviting.

One of the topics the speakers touched on was the problems of translation, and as I listened I was struck by the simple fact of the various ways the panelists had of speaking: quickly or slowly, with a variety of accents in English. I recalled how many international conferences I had been to where speakers made their presentations in a language that was not their first, and the occasional difficulties of expressing and understanding in a supposedly common language.

When it comes to written language, in a variety of scripts, the problems become visual as well as verbal. How does a user of a minority language in a complex script input their words? One aspect of this was dealt with in Tom Mullaney’s book The Chinese Typewriter (a follow-up, The Chinese Computer, is due out from MIT Press next year). Alolita Sharma discussed the role of the profit motive in corporations that might invest in linguistic support for languages with complex scripts. Thomas Phinney talked about the practical requirements of creating fonts for any script; in particular, he described the complexities of designing a font that supports all the African languages that use the Latin script (easily two or three times more characters than even the most extensive European Latin character set). Shumin Zhai described a project that had used data from multilingual Wikipedia to enable an input method called “shape-writing” (using pen strokes or swipes on a graphical keyboard) rather than hitting keys. Deborah Anderson’s Script Encoding Initiative (SEI) deals directly with language communities to get their input and buy-in for digital encoding. Andrew Glass, who works extensively with designing fonts to support historic scripts, noted wryly that, for a script with no contemporary users, “it’s hard to get feedback from the user community!”

The project’s next event will be Face/Interface on December 1–2, 2023, set to take place both in-person and via livestream.

Links: